|

I’ve been thinking a lot about why classical music institutions and organizations have difficulty adequately engaging with the artistic work of non-white musicians. I believe it comes down to the degree of intentionality we’re willing, ready, and capable to bring to not just what we do, but also how we go about it. While reading Pat Spencer’s article about Noel Da Costa’s Blue-Tune Verses and Claude Debussy’s Syrinx in a 2020 New York Flute Club newsletter,[1] I was struck by this question: Can we talk about a work by a non-white composer without referencing whiteness, without praising a non-white musician’s proximity to whiteness or their fluency in whiteness? Why do we fall back on that framing at all? It’s easy to question the utility of a lens of whiteness when we come across references to Joseph Bolougne, the Chevalier de Saint George, as the “Black Mozart.” How odd to be nicknamed after someone younger than yourself—especially someone whose work you influenced![2] On top of being forbidden to take his father’s title or become director of the Académie Royale de Musique due to racism in France, Bolougne’s nickname robs him of his own identity musically. His value, according to his nickname, is that he was musically skilled just like Mozart, even though he happened to be Black. The nickname masterfully praises Bolougne while holding him at arm’s length precisely because of his otherness. Such a framing may become even more uncomfortable when we think of it in terms of gender. Emilie Mayer was similarly referred to as the “female Beethoven.”[3] She was musically skilled like Beethoven, even though she happened to be female. Louise Farrenc is another composer whose value was touted in relation to another man—during her lifetime people described her music as being like that of Robert Schumann. What would it mean, though, if we were to say that Robert Schumann’s work is like Farrenc’s? Does the inverse sound wrong? Revisionist? Empowering? Historically accurate?[4] But let’s set these specific musicians aside and probe the more insidious question their examples raise. It is a question which lurks every time we consider the diversity of our programming, our syllabi, our reading lists, and our artist rosters: Why can’t our understanding of either of these composer’s value exist without being propped up by the men whose pale bodies litter the historical landscape around them? The way we frame an idea matters, because it amplifies and reinforces our understanding of the world, ourselves, and our values. What I’m talking about is the practice of centering whiteness (and, often, more precisely white maleness). Centering whiteness stands at odds with the aims of social justice, but it is something the practices of our field almost always rest upon. Centering How we tell stories is part of how we create our identities. We affirm our identities. We project our identities. We proclaim our identities. The stories we tell reaffirm who we believe we are, create space for others to see us as we choose to be seen, and shape the world for others around us to exist in. Every story has a center, a viewpoint or concern that is emphasized by its very center-ness. The center is revealed by whose stories are told, whose values are referred to. We tell stories every time we program a concert, every time we assign a textbook, every time we price tickets to one concert higher than tickets to another: “A contemporary of Beethoven” “Debussy-like harmonies” Schenkerian foregrounding… Gershwin-like jazz style “Just as good as…” “You could close your eyes and not know it’s…” It’s not just that we praise—it’s how. How we tell stories about music creates a framework for others to learn from, to build upon, and to understand what music is, what it means, and what music is worth paying attention to. When we tell stories of the musicians who matter to us by using whiteness as an anchor, we reaffirm that whiteness is the norm, that white is right—that a non-white musician’s value is contingent upon their proximity to “good” musicians (who all happen to be white). Why do we center? When I teach music appreciation, I always do a lesson on bias to awaken my students’ engagement of historical texts—words, of course, but also images, fashion, and sound. I want my students to understand the bias implicit in every text (and in every word they’ll write in my class). We often throw around the word “bias” like it’s a bad thing: You’re so biased! Don’t be biased! Fair and balanced! But bias just means perspective, and that’s an inescapable aspect of the human condition. Perspective is where we’re looking from: our position relative to what we’re looking at. Our position as people comes from our cultural upbringing, our geography, our life experiences, how others have treated us (based on our gender, our sexuality, our ethnicity, our bodies, our intelligence, our physical abilities, our personalities…). The list is infinite because human experience is so beautifully messy. The sum of all this infinitude is our perspective—Pierre Bourdieu refers to the “situatedness” of our listening, our hearing, our looking. Our perspective—our bias, our situatedness—is the place from which we engage with the world. It’s framed by how we’ve learned to be in the world: what words to use, what to pay attention to, how to think. The tropes and patterns of speech we fall into. The assumptions we make. Our frame of reference for understanding why something is important. That’s why centering of whiteness is so hard to break away from, especially when we seek to diversify our musical work. In the US, specifically, the “norm” is whiteness: the color of Band-Aids. Aperture settings on a camera. Facial recognition algorithms. Love interests and leading actors in TV and movies. Hands in stock photos and recipe videos. It’s the perspective we’re enculturated into—we learn to see the world and orient ourselves in the structures that surround us as we open our eyes. White (and white-presenting) individuals see themselves represented in that world. Individuals who are not white—in addition to systemic racism that creates barriers to education, employment, and physical safety—are implicitly told, over and over again by the structures and media aligned with power and money all around that this world is not meant for you. What’s the goal?

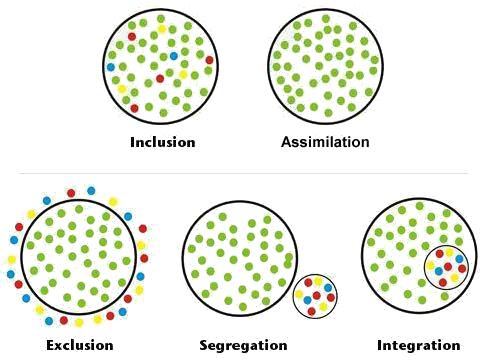

We must meet this reality with intentionality. Diversity isn’t enough—it’s lip service that feels like a more substantial effort than it really is, precisely because of the centering of whiteness that defines our world. Diversity doesn’t fix how we tell our stories. Diversity reinforces the “Black” in “Black Mozart” and not the Bolougne. The real goal we should be working towards is inclusion, and that’s harder to reach. Inclusion and uplift require decentering whiteness—and often decentering oneself (or even one’s organization) if your perspective is already in a position of power. Let’s imagine this with a metaphor of eating. If you host a party and only invite people you already know, that’s exclusion. “They can just throw their own party,” you say. That’s segregation. Diversity means inviting someone to the table—but you still own the table. You probably still plan the menu (it is your table, after all). It could be the most delicious meal ever, but it might not accommodate everyone’s dietary restrictions or preferences. Not everyone will be able to participate in that meal, even if they’re present. There’s also no way that you as the host could reasonably anticipate or accommodate everyone’s food needs. That’s integration. Inclusion means asking others where they want to build a table together and letting everyone bring their own favorite food to share. The meal won’t be what any one individual planned, but everyone will come away satisfied, able to eat, and the end result will be beyond what anyone in attendance could have imagined, created, or achieved on their own. If this sounds like a slow process, it is. If it sounds like something that would lead to the future we need, it is.[1] Back to music Diversity is easier than inclusion. That’s probably why we talk about it a lot. It’s low-hanging fruit. Tokenism is diversity. Programming one or two non-white artist in a year-long season is diversity. Feeble, but the box gets checked. How many of us have sat in administrative meetings calculating the percentage of non-white people on a Board, on a concert program, or in an audience? In the rush to diversify our concert lists, to “rediscover” a work that’s been ignored for decades, or book artists for a show, we must ground ourselves in practices that engender social justice through uplift—through decentering, through intentionality, through inclusion. This means that if we want to do justice to work of musicians whose identities are typically marginalized in the music industry and Western canon, we cannot tell their stories as if either their marginalized identity is the most interesting thing about them, as if they are in defiance of the ineptitude of all others who share their identity who couldn’t “hack” it, as if their similarity to a beloved white musician is why they’re worth paying attention to at all. When we’re drawn to music, we grapple with why and we find our story to tell, hoping that others may find it useful, too. Anything we’re relying on to make the case for a musician’s work—musical analysis, historical precedent, biographical details—always communicates bias and values beyond simply what we’re saying. We must take care that the support we offer the music we uplift actually serves our goal of uplift and doesn’t add an asterisk of otherness or of less-than. A musician’s work is valuable because music is human. Human beings are valuable. Full stop. Uplift is delicate work because the thing we’re working with is fragile. It’s fragile from years—centuries—of being beaten down, fragile because it’s had to survive without support, without shelter, without protection. So, uplift must be gentle, it must be intentional, it must be careful, lest we create more fragile pieces we’ll have to sweep up later. [1] Pat Spencer, “Noel Da Costa’s Blue-Tune Verses” https://nyfluteclub.org/uploads/newsletters/2020-2021/20-October-NYFC-Newsletter-final-p7-low.pdf [2] As Gabriel Banat pointed out in 1990, Mozart’s K.364 (1778) borrows a gesture that frequently appears in Bolougne’s solo violin works. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/779385?seq=1). See also Marcos Balter, “His Name Is Joseph Bolougne, Not “Black Mozart” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/22/arts/music/black-mozart-joseph-boulogne.html [3] Actually, there were a lot of “[adjective]-Beethovens” in the 19th century. He was used as a frame of reference for everything musically monumental, kind of like the question, “Who’s the greatest player of all time, Michael Jordan or LeBron James?” It’s helpful to have a frame of reference when a precocious or powerful figure comes along, someone who upends or expands our understanding of what is possible in a field. It’s also an act of reverence for the one serving as the frame of reference. But what does it mean in music when our frame of reference is always white people? [4] R. Schumann admired Farrenc’s work—the influence plausibly could have flowed this way. [1] See here for a distinction between outreach and engagement. http://www.communitypowermn.org/the_difference_between_community_engagement_and_marketing#:~:text=The%20word%20outreach%20implies%20that,outreach%20takes%20capacity%20and%20effort.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed